We live in a world where people aspire to look successful rather than to actually be. Measuring success by the number of social media followers, people tend to imitate stereotypically desirable online personas - defined mainly by a luxurious lifestyle -, craving desperately the validation of other people. This vast social behavioural trend, explains in a parallel manner the principle and essence of the counterfeit goods market as well as it’s potential correlation to its current most profitable days. According to The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the global market in counterfeit goods is worth nearly a trillion dollars (USD) a year. Nearly a trillion dollars a year in their very own independent market, partially overlapping with the legitimate global economy.

“the global market in counterfeit goods is worth nearly a trillion dollars a year”

For decades, fashion labels have been battling against counterfeiting in what seems to be an un-winnable war. A war against a supposedly harmless market, which steals creative originality and profits, as well as undermines luxury fashion’s prestige of craftsmanship and exclusivity. Endless lawsuits, secret police operations and anti-counterfeit technologies are just a few of the ‘weapons’ used against by the fashion industry. Specifically, according to London-based researcher Visiongain, apparel makers spent approximately $6.15 billion on anti-counterfeit technologies in 2017 alone. From Salvatore Ferragamo’s passive radio-frequency identifications tags in the left sole of each pair of shoes it produces, to Chanel’s hologram stickers with unique serial numbers in the lining of its handbags, fashion labels have been acutely trying to sustain and establish the authenticity of their products for years.

Once upon a time, buying forged goods was an intended and aware stroll in a particular corner of a street or the back-room of a store, however like much of 21st century commerce, the counterfeit goods market primarily lives online. Websites covertly or overtly selling luxury replicas; fakes abound on online auction sites like eBay, Amazon and AliExpress; Instagram boutiques using end-to-end encryption messenger apps such as Telegram or WhatsApp to communicate directly with customers. The internet is simply being used as a ‘massive amplifier’ for the counterfeit market, shedding light on the need for companies to adopt comprehensive anti-counterfeiting strategies and cross-sector collaborations to stop offenders.

The immoral nature and negative effects of counterfeiting on the fashion industry are indeed widely known. Infringed trademarks and copyrights, lost profits, lost jobs, usage of toxic materials, pollution, deplorable working conditions, unaware tricked customers, even money laundering. However, does this battle exist because counterfeiting actually has such a tremendous direct impact on these multi-million fashion companies, or is it just fought on an ethical and theoretical basis?

Primarily, the counterfeit market provides all these fashion brands with free advertising both through its online and offline presence. Particularly, the quality of counterfeits has become so high that fakes are nowadays often indistinguishable from their legit counterparts. As Alibaba’s founder and executive chairman, Jack Ma, stated referring to the ‘yuandan goods’, “The fake products today are of better quality and better price than the real names. They are exactly the [same] factories, exactly the same raw materials, but they do not use the same names.” Therefore, for a consumer to be exposed to these identical forged product, triggers the exact same reaction as to the real one; a subconscious desirability due to the ‘proven’ success of the -in this case- mimicked fashion brand. Even though most people would like to think that they are terribly original, consuming behaviour is indeed heavily based on imitation, proving that these counterfeits products might actually be more profitable for the company rather than paying an influencer to wear them, as the resistance barrier of direct marketing doesn't exist.

As in every market, the counterfeit goods are consumed for different reasons. Largely, knockoffs are acquired by people who either can’t afford the real price or by people who don’t want to spend a tremendous amount of money for a designer’s product, even if they have the funds to. Of course, luxury fashion is not only about the price tag. It’s about the craftsmanship, the extreme accuracy of detail, as well as a holistic shopping experience, from the service a customer receives in store down to the packaging. Nonetheless, luxury fashion prices nowadays are often unreasonably high. For instance, there is no logical explanation or justification behind an 80% cotton and 20% polyester Vetements hoodie costing £660. Therefore, as Jack Ma stated, if the production of a lot of these counterfeits are made in the exact same factories with the same materials, then why is it unreasonable for a person to spend probably £100 instead of £700 for the almost exact same product?

Of course, as an anti-luxury fashion representative, Guram Gvasalia, the co-founder of Vetements, in an interview for the New York Times he disclosed not only to be okay with the counterfeit market, but also that he admires the creativity hidden behind it. Specifically, Gurum said, "It’s funny because we see our things, but they have been changed. For example, we had a hooded dress in green with writing on the arms, and I looked online and saw they had turned it into a hoodie. They do things that are closer to the originals, but sometimes they become very creative."

The loss of a brand’s potential profits is another widely used argument when it comes to the moral nature of the counterfeit goods market. It is argued that if forged goods are being purchased, all these legitimate companies lose potential profit, which eventually can trigger a catastrophic chain reaction of money within the company. People lose their jobs and at last even the brand cannot sustain itself. Truly, this argument is indeed accurate and comprehensive, however only on a theoretical basis. Undoubtedly, counterfeits infringe on a brand’s profits but it’s almost impossible to accurately determine the extent to which it affects it. Every penny spent on a counterfeit doesn’t necessarily mean that it was destined to be spend on its legitimate counterpart. Therefore, once again a counterfeit consumer might not be directly profiting the legitimate manufacturer, although as mentioned above, the free advertisement it offers is probably more profitable in the long run.

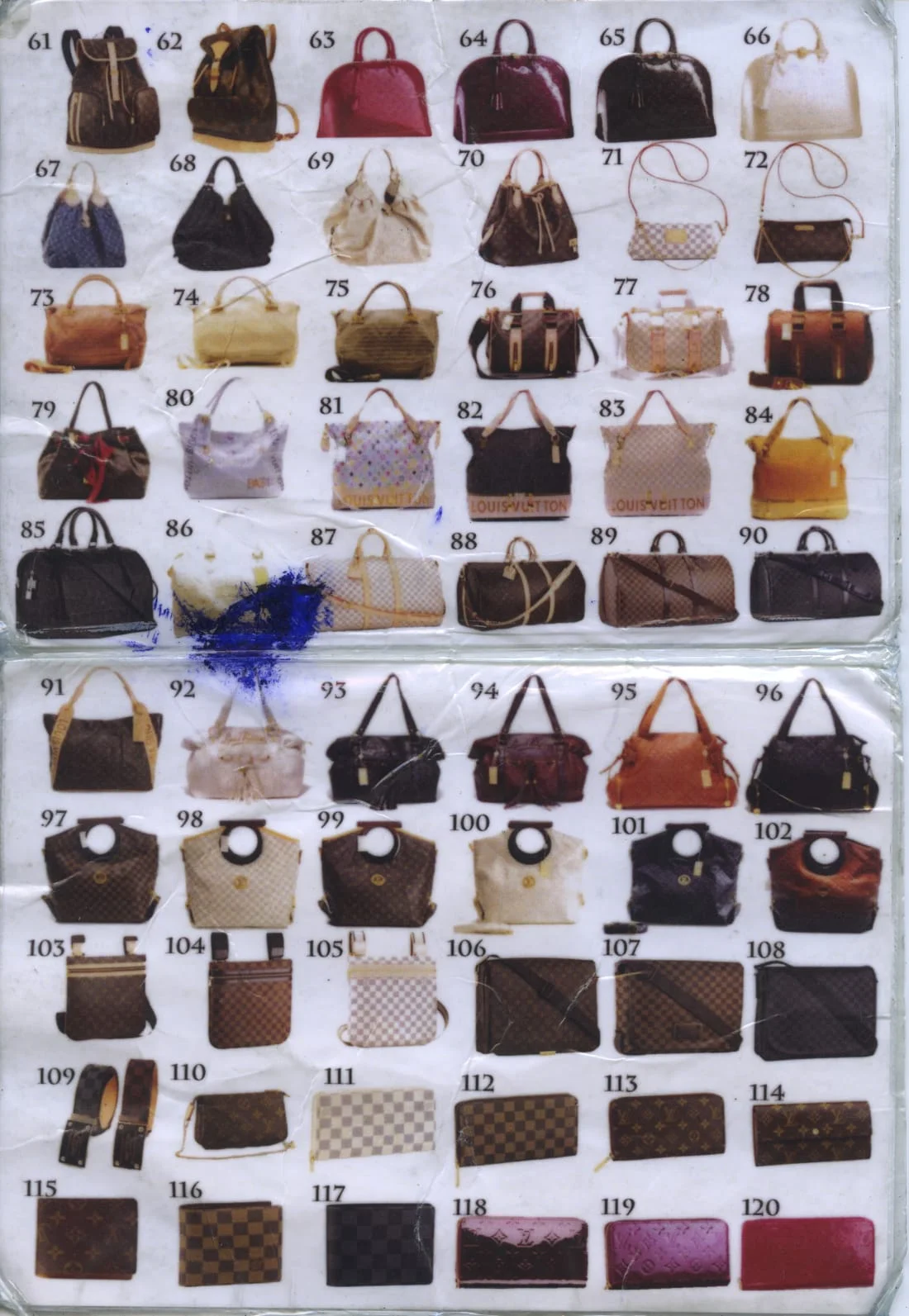

Apart from free advertising, counterfeits have also been proven to have a direct effect on their buyers themselves. Particularly, Renee Richardson Gosline, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, conducted a two-and-a-half year long study that focused and documented 112 women that attended “purse parties”, where they would buy counterfeit handbags. Through her study, Gosline found that nearly half of the 112 party-goes abandoned their counterfeits and decided to purchase an authentic luxury brand item within two and a half years. These replica handbags worked more as a gateway purchase rather than a substitution for their legit counterparts. As Gosling states, “On some level, these women are uneasy about the fake bag on their arm. As Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell sang, their counterfeits help them realise that there “Ain't Nothin’ Like the Real Thing, Baby.”

“every penny spent on a counterfeit doesn’t necessarily mean that it was destined to be spend on its legitimate counterpart.”

Fashion is a complex market, and counterfeit fashion is just as complex. Regardless of pros and cons, the counterfeit goods market is indeed a despicable crime, unfortunately harming many more than just the companies whose profits are affected and whose creative work is infringed. There is though a symbiotic relationship between the two. No-one knows or can predict the resonance that all these luxury brands would have without counterfeits, or the quality and the attention to detail of the genuine products if they didn’t have to desperately prove and establish their authenticity. The battle against counterfeiting will continue, and surely there will be some ‘victories’ along the way. However, is it all just symbolic?